Cortisol response to synacthen stimulation is attenuated following abusive head trauma.

Natasha L Heather, José G B Derraik, Christine Brennan, Craig Jefferies, Paul L Hofman, Patrick Kelly, Rhys G Jones, Deborah L Rowe, Wayne S Cutfield

文献索引:Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 77(3) , 357-62, (2012)

全文:HTML全文

摘要

Child abuse and other early-life environmental stressors are known to affect the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. We sought to compare synacthen-stimulated cortisol responses in children who suffered inflicted or accidental traumatic brain injury (TBI).Children with a history of early-childhood TBI were recruited from the Starship Children's Hospital database (Auckland, New Zealand, 1992-2010). All underwent a low-dose ACTH(1-24) (synacthen 1 μg IV) test, and serum cortisol response was compared between inflicted (TBI(I) ) and accidental (TBI(A) ) groups.We assessed 64 children with TBI(I) and 134 with TBI(A) . Boys were more likely than girls to suffer accidental (P < 0·001), but not inflicted TBI. TBI(I) children displayed a 14% reduction in peak stimulated cortisol in comparison with the TBI(A) group (P < 0·001), as well as reduced cortisol responses at + 30 (P < 0·01) and + 60 min (P < 0·001). Importantly, these differences were not associated with severity of injury. The odds ratio of TBI(I) children having a mother who suffered domestic violence during pregnancy was 6·2 times that of the TBI(A) group (P < 0·001). However, reported domestic violence during pregnancy or placement of child in foster care did not appear to affect cortisol responses.Synacthen-stimulated cortisol response is attenuated following inflicted TBI in early childhood. This may reflect chronic exposure to environmental stress as opposed to pituitary injury or early-life programming.© 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

相关化合物

| 结构式 | 名称/CAS号 | 分子式 | 全部文献 |

|---|---|---|---|

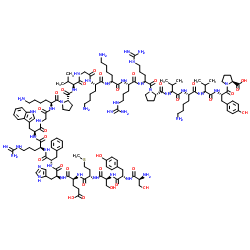

|

替可克肽

CAS:16960-16-0 |

C136H210N40O31S |

|

An LC-MS/MS method for steroid profiling during adrenal veno...

2015-01-01 [J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 145 , 75-84, (2015)] |

|

The relationship between vitamin D status and adrenal insuff...

2013-05-01 [J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98(5) , E877-81, (2013)] |

|

Free and total plasma cortisol measured by immunoassay and m...

2013-05-01 [J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98(5) , 1883-90, (2013)] |

|

Comparison of IV and IM formulations of synthetic ACTH for A...

2012-01-01 [J. Vet. Intern. Med. 26(2) , 412-4, (2012)] |

|

Estimation of maximal cortisol secretion rate in healthy hum...

2012-04-01 [J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97(4) , 1285-93, (2012)] |